Dyslexia Signs Checklist

This checklist helps identify potential signs of dyslexia in children. Based on research, dyslexia affects 15-20% of students worldwide. Check symptoms you observe. Note: This is not a diagnosis, but can help determine if professional evaluation is needed.

Results

Note: This tool identifies potential signs. Professional evaluation is needed for diagnosis. Early intervention is crucial - research shows structured literacy programs can improve reading accuracy by 42% with proper support.

One in five students struggles with a learning disability-and most of them aren’t even diagnosed until they’re falling behind in class. The most common one? dyslexia. It’s not about being lazy or not trying hard enough. It’s not about intelligence. It’s about how the brain processes language, especially when it comes to reading, spelling, and writing. In classrooms across Ireland, the UK, and the US, dyslexia shows up in the same quiet ways: a child who reads slowly, skips small words, mixes up letters like b and d, or spends hours on homework that should take half the time.

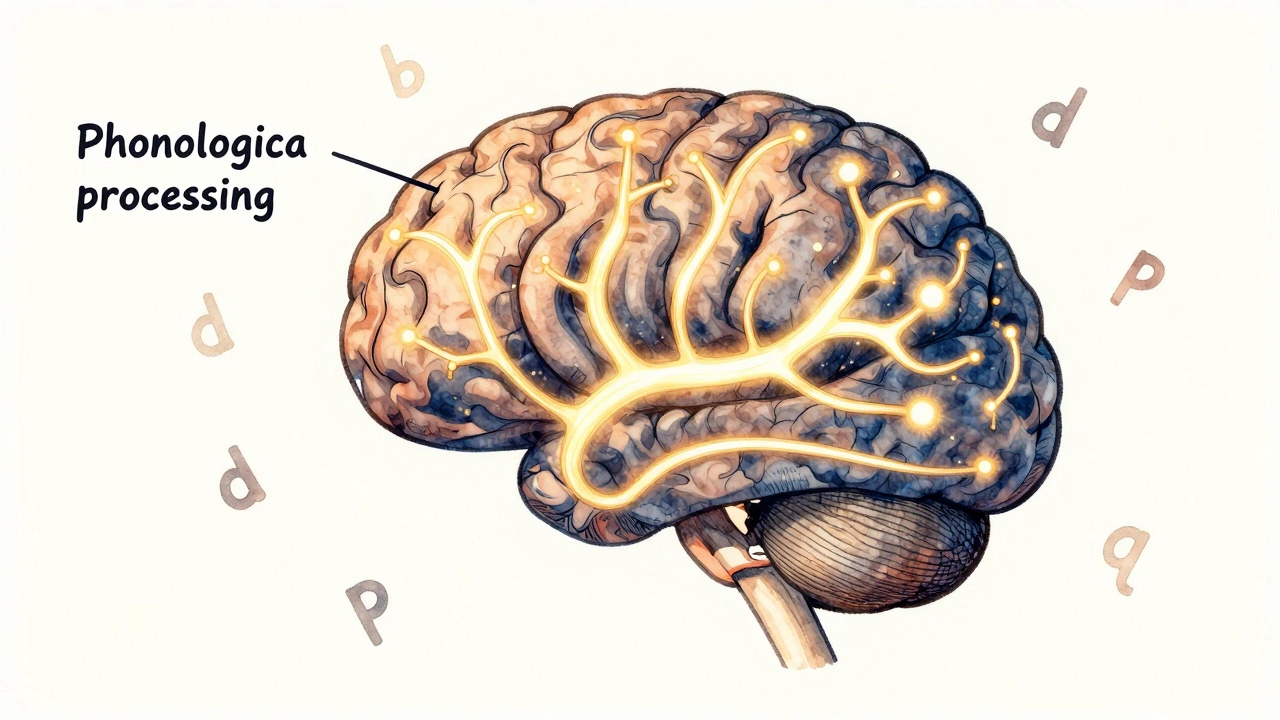

Dyslexia Isn’t Just ‘Reversing Letters’

Most people think dyslexia means seeing letters backward. That’s a myth. Real dyslexia is a language-based learning difference. It’s not visual. It’s neurological. Kids with dyslexia have trouble connecting the sounds of spoken language to the letters on the page. This is called phonological processing. When you hear the word ‘cat,’ your brain automatically breaks it down into /k/ /a/ /t/. For a child with dyslexia, that step is glitchy. They hear the word fine, but connecting it to written form? That’s where things break down.

That’s why they might spell ‘because’ as ‘becuz’ or read ‘horse’ as ‘house.’ It’s not carelessness. It’s the brain taking a longer, more confusing path to decode words. The result? Reading becomes exhausting. They avoid books. They hate reading aloud. They’re labeled ‘not trying’ when what they really need is the right kind of support.

How Common Is It Really?

Research from the National Institutes of Health in the US shows that dyslexia affects between 15% and 20% of the population. That’s one in five students. In Ireland, the Department of Education estimates around 18% of primary school children show signs of dyslexia, though only half are formally identified. Why? Because schools often wait until a child is failing before acting. By then, the damage to confidence is already done.

It’s the same story in England and Scotland. Teachers notice the patterns: a bright kid who can explain complex ideas out loud but can’t write them down. A student who remembers everything from a story read to them but can’t answer questions from the text. These aren’t random struggles. They’re classic signs of dyslexia.

Other Learning Disabilities-But None Are This Common

There are other learning disabilities, sure. Dyscalculia, which makes math numbers feel meaningless. Dysgraphia, which turns handwriting into a nightmare. ADHD, which isn’t a learning disability but often coexists with one. Processing disorders, auditory or visual, that slow down how fast information gets understood.

But none come close to dyslexia in numbers. Dyscalculia affects about 3-7% of students. Dysgraphia? Maybe 10%. ADHD? Around 5-7% in school-aged kids. But dyslexia? It’s the big one. It shows up in every classroom, every school, every town. And because it’s so common, many schools still don’t know how to handle it properly.

What Happens When It’s Not Supported?

Without the right help, dyslexia doesn’t just affect reading. It affects everything. A child who can’t read fluently starts to hate school. They stop raising their hand. They act out. They withdraw. By secondary school, many are labeled ‘underachievers’-even though their IQ is average or above.

Studies from Trinity College Dublin show that students with undiagnosed dyslexia are three times more likely to drop out of school than their peers. They’re more likely to develop anxiety or depression. They’re less likely to go to college-even if they’re smart enough.

It’s not the disability that holds them back. It’s the lack of understanding. A child with glasses doesn’t get told they’re ‘bad at seeing.’ But a child with dyslexia? They’re told to ‘try harder.’ That’s cruel. And it’s unnecessary.

What Works? The Right Kind of Teaching

Dyslexia doesn’t go away. But it can be managed-with the right teaching. The most effective method is structured literacy. That means explicit, systematic instruction in phonics, decoding, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. It’s not about tricks or apps. It’s about teaching the rules of language step by step.

Programs like Orton-Gillingham, Wilson Reading System, and Barton Reading & Spelling have been proven to work. They’re not magic. They’re just clear. They break reading into small pieces. They use multi-sensory techniques-seeing, saying, touching, hearing-all at once. A child traces letters in sand while saying the sound. They clap out syllables. They build words with tiles.

And it works. A 2023 study in the Journal of Learning Disabilities found that students who got 90 minutes a week of structured literacy for six months improved their reading accuracy by 42%. That’s not a small gain. That’s life-changing.

What Schools Still Get Wrong

Many schools still rely on ‘whole language’ approaches-where kids guess words from pictures or context. That doesn’t work for dyslexic learners. They need structure. They need repetition. They need to know the rules.

Another mistake? Waiting for a child to fail before offering help. In Ireland, children aren’t eligible for special education support until they’re two years behind. That’s too late. Early identification-by age six or seven-makes all the difference.

Teachers need training. Not a one-day workshop. Real, ongoing professional development. Right now, only 30% of primary teachers in Ireland have received formal training in dyslexia. That’s not enough.

What Parents Can Do

If you suspect your child has dyslexia, don’t wait. Talk to the school. Ask for a screening. You don’t need a formal diagnosis to start getting help. Many schools offer early intervention programs.

At home, read aloud to your child. Even if they’re older. Let them hear how language flows. Use audiobooks. Let them choose books they care about-even if they’re picture books. Build confidence. Celebrate small wins. A new word read correctly? That’s a victory.

And don’t let anyone tell you it’s ‘just a phase.’ Dyslexia doesn’t disappear. But with the right tools, your child can learn to read, write, and thrive.

Dyslexia Isn’t a Barrier-It’s a Different Path

Think of dyslexia like being left-handed in a right-handed world. It’s not broken. It’s just different. Many of the world’s greatest thinkers, artists, and entrepreneurs had dyslexia: Richard Branson, Steve Jobs, Agatha Christie, Pablo Picasso. They didn’t overcome it by ‘trying harder.’ They found ways to work with it.

Today’s students with dyslexia don’t need to be fixed. They need to be understood. They need teachers who know how to teach them. They need schools that give them time, tools, and trust.

One in five students has dyslexia. That means in every classroom of 30, six kids are struggling silently. They’re not slow. They’re not dumb. They’re just wired differently. And with the right support, they can do anything.

Is dyslexia the most common learning disability in students?

Yes. Dyslexia affects 15% to 20% of students worldwide, making it by far the most common learning disability. It’s more prevalent than dyscalculia, dysgraphia, or processing disorders. In Ireland and the UK, around one in five children shows signs of dyslexia, though many go undiagnosed.

Can a child outgrow dyslexia?

No, dyslexia doesn’t go away. But with the right teaching, children can learn strategies to read and write effectively. Their brain learns to work around the challenge. Many adults with dyslexia read fluently-they just take longer and rely on tools like text-to-speech or spell-check. It’s not cured. It’s managed.

Do all children with dyslexia struggle with spelling?

Almost all do. Spelling is one of the hardest areas because it requires remembering letter patterns, rules, and exceptions. A child with dyslexia might spell the same word three different ways in one paragraph. That’s not carelessness-it’s the brain struggling to store and retrieve spelling patterns. Structured literacy programs help fix this over time.

Can a child with dyslexia be good at math?

Absolutely. Dyslexia affects language processing, not logic or reasoning. Many students with dyslexia excel in math, especially when it’s taught visually or through hands-on methods. Some even find math easier than reading because it relies less on decoding words and more on patterns and symbols. But if math word problems are involved, that’s where the language barrier kicks in.

What should I do if I think my child has dyslexia?

Talk to your child’s teacher and ask for a screening. You don’t need a formal diagnosis to start support. Many schools offer early intervention programs. At home, read aloud together, use audiobooks, and avoid pressuring them to read alone. Celebrate effort, not just results. If needed, seek an assessment from a psychologist or educational therapist trained in dyslexia.

Write a comment